Πηγές

Μια επιλεγμένη συλλογή πηγών για τη διάγνωση, τη θεραπεία και τη συνεχή αντιμετώπιση ατόμων με πνευμονική νόσο από μη φυματικά μυκοβακτηρίδια (NTM-PD) καθώς και υποκείμενα νοσήματα που αποτελούν παράγοντες κινδύνου.

Στην παρούσα ενότητα, μια βιβλιοθήκη πηγών που αναπτύσσεται συνεχώς και περιλαμβάνει βίντεο, διαδικτυακά σεμινάρια, podcast και άρθρα, προσφέρει αναλυτικές πληροφορίες για τη νόσο NTM-PD και συγκεκριμένα είδη NTM, καθώς και στοιχεία που θα σας βοηθήσουν να αναγνωρίσετε τους ασθενείς σε κίνδυνο για NTM και οδηγίες για το τι πρέπει να κάνετε στην περίπτωση διάγνωσης NTM.

Άρθρο

Κατανοώντας τους παράγοντες κινδύνου για NTM-PD

Read time: 69 mins

Οι κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες ERS/ATS/ESCMID/IDSA για τη NTM-PD 2020 παρουσιάζουν πώς γίνεται η διάγνωση ενός ασθενή με NTM-PD, με βάση τις αξιολογήσεις των κλινικών, απεικονιστικών και μικροβιολογικών δεδομένων.

Άρθρο

Read time: 16 mins

Επισκόπηση συζητήσεων στο ECCMID 2021 με αντικείμενο τη NTM-PD

Άρθρο

Read time: 5 mins

Η μελέτη CONVERT [NCT02344004] αξιολόγησε την αποτελεσματικότητα και την ασφάλεια της εισπνεόμενης λιποσωμιακής αμικασίνης (ALIS [διάλυμα για εισπνοή με εκνεφωτή ARIKAYCE liposomal 590 mg]) σε ενήλικες ασθενείς με NTM-PD ανθεκτική στη θεραπεία

Άρθρο

Read time: 9 mins

Επισκόπηση κλινικών δοκιμών για την NTM-PD οι οποίες είναι σε εξέλιξη ή ολοκληρώθηκαν πρόσφατα

Άρθρο

Επίδραση των μη φυματικών μυκοβακτηριδίων σε ασθενείς με παράγοντες κινδύνου

Read time: 5 mins

Τα μη φυματικά μυκοβακτηρίδια (NTM) μπορούν να προκαλέσουν σοβαρή πνευμονοπάθεια στους ασθενείς με παράγοντες κινδύνου, έχοντας σημαντικό αντίκτυπο στην ποιότητα ζωής τη νοσηρότητα και τη θνησιμότητα και επιταχύνοντας την προοδευτική εξέλιξη της ασθένειας

Άρθρο

Read time: 5 mins

Η αντιμετώπιση της πνευμονικής νόσου από μη φυματικά μυκοβακτηρίδια (NTM-PD) με αντιμικροβιακούς παράγοντες προσφέρει τη δυνατότητα της ίασης. Σε ασθενείς που πληρούν τα κλινικά, απεικονιστικά και μικροβιολογικά διαγνωστικά κριτήρια για NTM-PD.

Άρθρο

Read time: 7 mins

Η πνευμονική νόσος που οφείλεται στο σύμπλεγμα άτυπων μυκοβακτηριδίων MAC (MAC-PD) παρουσιάζει προβλήματα στη διάγνωση, καθώς τα συμπτώματα είναι παρόμοια με εκείνα υποκείμενων πνευμονικών νοσημάτων.

Άρθρο

Κατανοώντας τις βέλτιστες πρακτικές στην πνευμονική νόσο από το σύμπλεγμα MAC (MAC-PD)

Read time: 10 mins

Η θεραπεία της πνευμονικής νόσου από μη φυματικά μυκοβακτηρίδια (NTM-PD) ποικίλλει ανάλογα με το είδος των μυκοβακτηριδίων, την έκταση της νόσου, τα αποτελέσματα από τη δοκιμή ευαισθησίας σε αντιφυματικά φάρμακα και υποκείμενες συννοσηρότητες.

Άρθρο

Read time: 8 mins

Η πνευμονική νόσος από μη φυματικά μυκοβακτηρίδια (NTM-PD) εμφανίζεται όλο και συχνότερα και μπορεί να οδηγήσει στον θάνατο. Οι διεθνείς κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες του 2020 παρέχουν συστάσεις σχετικά με τα τέσσερα συχνότερα παθογόνα είδη NTM.

Άρθρο

Διαχείριση ασθενών στη διάρκεια μιας πανδημίας

Read time: 5 mins

Η πανδημία COVID-19 έφερε την τηλεϊατρική στο προσκήνιο του τομέα υγείας. Ο τομέας που σχετίζεται με την παρακολούθηση της πνευμονικής νόσου από μη φυματικά μυκοβακτηρίδια (NTM-PD) είναι ένας από τους πολλούς που ασπάστηκε αυτήν την αλλαγή.

Βίντεο

Κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA για τη NTM-PD 2020 – Παρουσίαση ειδικών

Stefano Aliberti, Christoph Lange, Eva Polverino, Nicolas Veziris, Charles Haworth and Jakko van Ingen

Η πνευμονική νόσος από μη φυματικά μυκοβακτηρίδια (NTM-PD) εμφανίζεται όλο και συχνότερα και μπορεί να οδηγήσει στον θάνατο. Οι διεθνείς κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες του 2020 παρέχουν συστάσεις σχετικά με τα τέσσερα συχνότερα λοιμογόνα είδη NTM.

Βίντεο

Ποιοι είναι οι ασθενείς που διατρέχουν κίνδυνο για MAC-PD

Οι υποκείμενες πνευμονικές παθήσεις ή η ανοσοκαταστολή αυξάνουν σημαντικά τον κίνδυνο νόσησης από MAC-PD. Δείτε σε αυτό το βίντεο τους ειδικούς να αναλύουν ποιοι είναι οι ασθενείς με παράγοντες κινδύνου και ποια τα ενδεικτικά συμπτώματα.

Βίντεο

Η απόφαση για το ποια είναι η κατάλληλη στιγμή για την έναρξη της θεραπείας στη MAC-PD εξαρτάται από πολλούς παράγοντες. Σε αυτό το βίντεο, ειδικοί διερευνούν το σκεπτικό και το χρονικό πλαίσιο για την έναρξη της θεραπείας.

Βίντεο

Συνεχής διαχείριση ασθενών με MAC-PD

Δείτε και ακούστε διεθνείς ειδικούς να διερευνούν τα βασικά στοιχεία στην εφαρμοζόμενη θεραπευτική μεταχείριση έως τη μετατροπή της καλλιέργειας και μετά από αυτήν.

Βίντεο

Τι πρέπει να γίνει στην περίπτωση αποτυχίας της θεραπείας

Σε αυτό το βίντεο, ειδικοί διερευνούν τις επιλογές που έχουν οι ιατροί για τη MAC-PD όταν η θεραπεία αποτυγχάνει.

Βίντεο

Μικροβιολογική κατάσταση κατά τη διάγνωση και τη θεραπεία της MAC-PD

Σε αυτό το βίντεο, ειδικοί μοιράζονται τις σκέψεις τους για τον ρόλο των μικροβιολογικών εξετάσεων στη διάγνωση, στον καθορισμό αποτελεσματικών θεραπευτικών στρατηγικών και στην καθημερινή παρακολούθηση με στόχο την αρνητικοποίηση της καλλιέργειας.

Βίντεο

Κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες για τη NTM-PD – Βασικές συστάσεις

Σε αυτό το βίντεο, οι Ευρωπαίοι εμπειρογνώμονες παρέχουν τις γνώσεις τους σχετικά με τις οδηγίες ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA 2020 για το NTM-PD, με έμφαση στο MAC-PD.

Βίντεο

www.RethinkNTM – Ποιος, γιατί και πότε; ERS 2020

Παρακολουθήστε το συνέδριο ERS 2020 με χορηγό την Insmed και ενημερωθείτε για τον ασθενή με παράγοντες κινδύνου για NTM-PD, τις προκλήσεις στη διαχείριση της NTM-PD και τις συστάσεις των κατευθυντήριων οδηγιών ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA 2020.

Βίντεο

Με το βλέμμα στο μέλλον - το μεταβαλλόμενο τοπίο της πνευμονικής λοίμωξης από MAC - WBNC 2020

Παρακολουθήστε το συνέδριο WBNC 2020 με χορηγό την Insmed και ενημερωθείτε για τις εξελίξεις στη διαχείριση της NTM-PD, τις συστάσεις των κατευθυντήριων οδηγιών ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA 2020 και τη χρήση της ALIS σε κλινικό περιβάλλον.

Συλλογή διαφανειών

Συλλογή διαφανειών με κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA για τη NTM-PD

Σε αυτή τη σύντομη συλλογή διαφανειών θα βρείτε μια επισκόπηση των οδηγιών ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA 2020.

αφίσα

Σύντομος οδηγός με κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA για τη NTM-PD

Βρείτε στον σύντομο οδηγό τσέπης τις συστάσεις των κατευθυντήριων οδηγιών ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA 2020 για την NTM-PD

Managing patients during a pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought telemedicine to the forefront of healthcare. The monitoring of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) is one of the many aspects of healthcare to adopt this change, with many patients trading in-person consultations with clinicians for video consultations, as well as sending sputum samples through the post for analysis. As a result of its success during the pandemic, many believe that soon telemedicine will form an integral part of healthcare.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about many changes to everyday life. Perhaps one of the more beneficial changes to arise during the pandemic is the switch to telemedicine. The idea of telemedicine has been around for a while, but the pandemic and the need for social distancing measures have provided the momentum to adopt this approach into routine practice.1,2

Telemedicine is the use of digital communications to provide remote support for patients to manage aspects of their health.1 The need to limit contact between individuals to reduce the risk of transmission during the pandemic has led to a rapid uptake of telemedicine around the world to help keep both patients and healthcare professionals (HCPs) safe while allowing continuation of routine care.2 Examples include a shift toward telephone and video consultations as well as patients providing laboratory samples through the post, which is currently the case for many patients with NTM-PD.

The management of patients with NTM during the pandemic represents a unique challenge because of the need for regular monitoring of these patients. During a symposium, ‘Looking ahead – the changing landscape of MAC lung infection’, at the 4th World Bronchiectasis & NTM Conference (WBNC) 2020, experts described how the management of NTM-PD has changed in their practices in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Eva Polverino (Vall D’Hebron University Hospital, Spain) explained that following an initial shock response in early 2020 as the pandemic took hold, there was a drive to maintain effective management of patients with NTM-PD during the pandemic, and so telemedicine was introduced. For her, it was important to decide with patients which tests and which visits were a priority, and which could be delayed. Stefano Aliberti (University of Milan, Italy) also emphasised the importance of the new international NTM management guidelines,4 which he believes have been one of the major steps forward in the management of NTM-PD, particularly during the pandemic. Not only have the guidelines helped in the management of NTM-PD, but also in raising awareness of the disease.

Patients with NTM-PD who are receiving treatment should typically be monitored with monthly sputum samples to assess treatment response. During the pandemic, many clinicians have found it more difficult to monitor their patients with NTM-PD, as patients cannot frequently travel to hospitals to deliver sputum samples. However, sputum samples can be sent through the post to enable effective monitoring. Patients are sent tubes for sputum collection that they then post to a laboratory for testing. Evidence has shown that sputum is stable at room temperature for at least 7 days,5 samples are good enough quality to be used for culture and there is no additional burden on laboratories to process these samples.

Telemedicine may be an appropriate option for those patients who are already diagnosed and in receipt of treatment but may be more difficult in those patients who develop symptoms of NTM-PD that may be vague or like those of their underlying lung conditions presenting virtually to their respiratory clinic or primary care physician. It is known that patients with NTM-PD who do not receive treatment, outcomes can be poor, and their health-related quality of life adversely affected,6,7 so encouraging patients with symptoms of NTM-PD to discuss these with their physician and for physicians to have an index for suspicion to test patients for NTM-PD is required; the role of telemedicine in these patients is yet to be fully explored and exploited.

Instead of postal sputum samples, some clinics such as the Policlinico of Milan attended by Stefano Aliberti have created systems with specific time-slots or local collection points where patients can regularly drop off their sputum samples for evaluation. In some vulnerable patients, sputum samples can be collected every 3 months, and it is up to the HCP and their patient to decide what is best.

The opinion from experts is that the management of patients diagnosed with NTM-PD who are already receiving antibiotic therapy during the pandemic has remained effective in most cases. This has been achieved through the use of community hubs for sputum collection or submission of sputum by mail to expert centres and development of COVID-19 free pathways within hospitals or COVID-19-free sites/units within hospitals. However, it is known that across healthcare in general there has been a reduction in the number of patients with symptoms presenting to healthcare professionals and delays in referred investigations8,9 but the impact of this on care for NTM-PD patients not yet diagnosed is unknown.

Indeed, in one survey among respiratory physicians, 95% of respiratory consultants said that the pandemic had a negative impact on respiratory care of non-COVID patients, and 88% said that waiting lists for routine respiratory care have increased, in some cases by more than 50%.10

The shift to telemedicine has facilitated patient and HCP safety during the pandemic and has had the additional benefit of improving patient outcomes in some cases.1,2 It has allowed continuation of routine care from the safety of the home, reducing the need for non-essential trips to the hospital.1 By increasing the ability for patients to self-manage their condition from home, telemedicine may also have helped minimise the load on healthcare systems, and some clinicians have been able to significantly increase the number of patients they can consult in a day.2,11 Moving forward in a post-pandemic world, telemedicine may have gathered enough traction to be maintained in the future as an integral part of healthcare.1 Taking experiences from the pandemic, telemedicine could pave the way for the development of more advanced healthcare solutions including using technologies such as wearable devices and smart phones to support routine care, transforming healthcare in the long term.2

Βιβλιογραφία:

- Ahmed S, et al. BMJ Innov 2020;6:252–4.

- Blandford A, et al. Lancet Global Health 2020;8(11):e1364–e1365.

- Looking ahead – the changing landscape of MAC lung infection, Insmed, 4th World Bronchiectasis & NTM Conference, 16–19 December 2020. http://www.world-bronchiectasis-conference.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/WBNC2020_Final_Programme_V1_2.pdf [Accessed March 2021].

- Daley CL, et al. Eur Respir J 2020;56:2000535.

- Pennings LJ, et al. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2018;92:309–10.

- Mehta M, et al. Respir Med 2011;105:1718–25.

- Yeung MY, et al. Respirology 2016;21:1015–25.

- Bower E. GP 5 May 2020. https://www.gponline.com/urgent-referrals-rejected-one-three-gps-during-covid-19-outbreak/article/1682282 [Accessed March 2021].

- British Medical Association. The hidden impact of COVID-19 on patient care the NHS in England. https://www.bma.org.uk/media/2840/the-hidden-impact-of-covid_web-pdf.pdf [Accessed March 2021].

- ITS Annual Scientific Meeting Press Release, Dec 3rd 2020. https://irishthoracicsociety.com/2020/12/its-annual-scientific-meeting-press-release-dec-3rd-2020/ [Accessed March 2021].

- Webster P. Lancet 2020;396(10231):1180–1.

Medical writing and editorial support was provided by Highfield, Oxford, UK. This support was sponsored by Insmed.

Medical writing and editorial support was provided by Highfield, Oxford, UK. This support was sponsored by Insmed.

CONVERT Study: The efficacy, sustainability and long-term safety of ALIS for patients with treatment-refractory MAC-PD

The CONVERT study [NCT02344004] evaluated the efficacy and safety of amikacin liposomal inhalation suspension (ALIS [ARIKAYCE liposomal 590 mg nebuliser dispersion]) in adult patients with treatment-refractory non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) caused by Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) in addition to oral guideline-based therapy (GBT) compared with oral GBT alone. ALIS plus oral GBT demonstrated high rates of culture conversion in 6-month data published in 2018 compared with GBT alone (29% vs 9%) and a follow-up study demonstrated culture conversions were often sustained and durable, and there were no new safety signals emerged with long-term use of ALIS.

MAC-PD is a difficult-to-treat pulmonary infection. When initial oral GBT fails, outcomes are poor and options are limited.1,2 ALIS is a novel amikacin formulation that penetrates alveolar macrophages and biofilms while limiting systemic exposure.3–5 ALIS is currently recommended by guidelines for patients with MAC-PD who fail to achieve culture conversion after at least 6 months of oral GBT in combination with oral GBT.6 ALIS has been previously tested in a Phase II study of treatment-refractory non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) where the addition of ALIS to standard oral GBT achieved higher rates on negative sputum cultures compared with oral GBT alone.7

CONVERT was a prospective, open-label, randomised trial that evaluated the efficacy and safety of daily ALIS in addition to oral GBT in patients with refractory MAC-PD compared with oral GBT alone. A total of 336 patients with amikacin-susceptible MAC-PD and MAC-positive sputum cultures after receiving at least 6 months of oral GBT were randomised at a 2:1 ratio to receive either ALIS plus oral GBT or oral GBT alone. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving culture conversion, which was achieved if patients had three consecutive monthly MAC-negative sputum cultures by Month 6 of the study. The study was conducted in 127 centres across 18 countries in North America, Asia-Pacific and Europe. Patients were mostly female (69.3%) with a mean age of 64.7 years and many patients had underlying bronchiectasis (62.5%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (14.3%) or both (11.9%). The majority of patients (89.9%) were receiving GBT at enrolment, with the remainder off treatment for 3–12 months. Most patients (69.3%) were on a three-drug regimen at baseline, with 54.9% on regimens which included a macrolide, ethambutol and a rifamycin.8

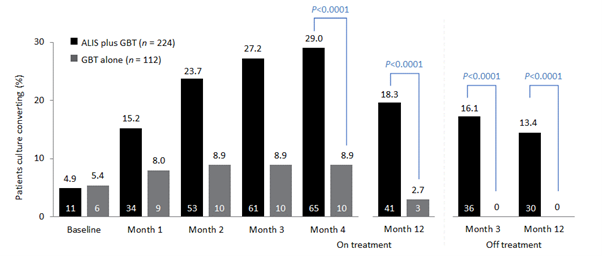

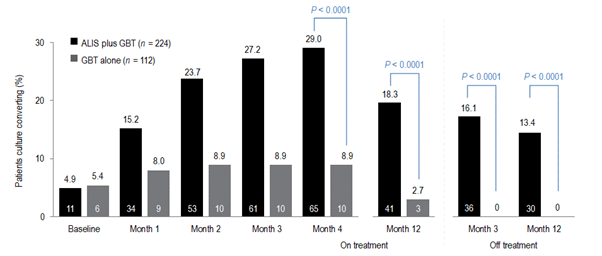

Initial results of the trial demonstrated the efficacy of ALIS in addition to oral GBT in achieving culture conversion by Month 6.8 Patients treated with ALIS in addition to oral GBT were almost four times as likely to achieved culture conversion by Month 6,8 with 29% (n=65/224) of patients on ALIS plus oral GBT achieving culture conversion compared with only 8.9% (n=10/112) on oral GBT alone (P<0.0001).8,9

In a follow-up study published in 2021, patients who achieved culture conversion by Month 6 continued treatment for an additional 12 months, followed by off-treatment observation in order to assess the sustainability and durability of culture conversion. Following 12 months of post-conversion treatment, 63.1% (n= 41/65) of converters in the ALIS plus oral GBT arm and 30.0% (n=3/10) in the oral GBT alone arm achieved sustained conversion (P=0.0644). In the intention-to-treat population, which includes patients who did not culture convert, 18.3% (n=41/65) of patients in the ALIS plus oral GBT arm achieved sustained culture conversion compared with only 2.7% (n=3/10) in the oral GBT alone arm (P<0.0001). Three months following end of treatment, 55.4% (n=36/65) of ALIS plus oral GBT culture-converted patients also achieved durable culture conversion whereas no patients on oral GBT alone achieved durable culture conversion (P=0.0017). In the intention-to-treat population, 16.1% (n=36/224) of all patients on ALIS plus oral GBT achieved durable culture conversion versus no patients treated with oral GBT alone (P<0.0001).9

Re-emergence of a MAC strain with an identical genotype to the strain identified on initiation of treatment may indicate relapse, particularly if this occurs within the first 8 months of treatment. At the end of treatment, only 7.7% (n=5/65) of patients on ALIS plus oral GBT had relapsed compared with 30% (n=3/10) of patients on oral GBT alone. In contrast, recurrence of MAC after 8 months of treatment may indicate reinfection, in which MAC has been reacquired from the environment, and is treated as a new MAC infection. In total, 4.6% (n=3/65) of patients on ALIS plus oral GBT were reinfected with MAC, compared with 10% (n=1/10) of patients on oral GBT alone.9

Treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) occurred mainly in the first 8 months of treatment and were mainly respiratory. Respiratory TEAEs were reported more frequently in the ALIS plus oral GBT arm and included dysphonia (61.5%), cough (41.5%), dyspnoea (21.5%), and haemoptysis (20.0%). Nephrotoxicity TEAEs were balanced between the two arms (n=2 in both arms) and ototoxicity-related TEAEs in the ALIS plus GBT arm were primarily tinnitus (10.8%) and dizziness (7.7%). Only four patients discontinued treatment because of TEAEs in the ALIS plus oral GBT converter arm. Three patients who achieved culture conversion died, all in the oral GBT alone arm.9

The CONVERT study showed that the addition of ALIS to oral GBT significantly increased the likelihood of culture conversion by Month 6 compared with oral GBT alone, providing the first evidence in a randomised trial in addition to the Phase II study of efficacy against treatment-refractory MAC-PD (Figure 1).8 In addition, culture conversion in patients treated with ALIS in addition to oral GBT was generally sustained and durable with low risk of relapse (Figure 1).9 Long-term exposure to ALIS did not present any new safety concerns, with most TEAEs consistent with administration of an inhaled add-on antibiotic and generally occurring in the first 8 months of treatment.9 Overall, these results highlight the clinical utility of ALIS in the management of patients with refractory MAC-PD.

Figure 1. Proportion of patients achieving culture conversion by the first month of conversion.8,9

Month 4 was the last time point at which the first of three negative sputum cultures could be achieved for a patient to be considered a converter at Month 6.

ALIS, amikacin liposomal inhalation suspension; GBT, guideline-based therapy.

Βιβλιογραφία:

- Griffith DE, Aksamit TR. Therapy of refractory nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2012;25:218–27.

- Jo K-W, Kim S, Lee JY, Lee SD, Kim WS, Kim DS, et al. Treatment outcomes of refractory MAC pulmonary disease treated with drugs with unclear efficacy. J Infect Chemother 2014;20:602–6.

- Rose SJ, Neville ME, Gupta R, Bermudez LE. Delivery of aerosolized liposomal amikacin as a novel approach for the treatment of nontuberculous mycobacteria in an experimental model of pulmonary infection. PLoS ONE 2014:9:e108703.

- Malinin V, Neville M, Eagle G, Gupta R, Perkins WR. Pulmonary deposition and elimination of liposomal amikacin for inhalation and effect on macrophage function after administration in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016;60:6540–9.

- Zhang J, Leifer F, Rose S, Chun DY, Thaisz J, Herr T, et al. amikacin liposome inhalation suspension (ALIS) penetrates non-tuberculous mycobacterial biofilms and enhances amikacin uptake into macrophages. Front Microbiol 2018;9:915.

- Daley CL, Iaccarino JM, Lange C, Cambau E, Wallace RJ Jr, Andrejak C, et al. Treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: an official ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA clinical practice guideline. Eur Respir J 2020;56:2000535.

- Olivier KN, Griffith DE, Eagle G, McGinnis JP 2nd, Micioni L, Liu K, et al. Randomized trial of liposomal amikacin for inhalation in nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195:814–23.

- Griffith DE, Eagle G, Thomson R, Aksamit TR, Hasegawa N, Morimoto K, et al. Amikacin liposome inhalation suspension for treatment-refractory lung disease caused by Mycobacterium aviumcomplex (CONVERT). A prospective, open-label, randomized study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;198:1559–69.

- Griffith DE, Thomson R, Flume PA, Aksamit TR, Field SK, Addrizzo-Harris DJ, et al. Amikacin liposome inhalation suspension for refractory Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease: sustainability and durability of culture conversion and safety of long-term exposure. Chest 2021; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.03.070

![]()

Medical writing and editorial support was provided by Highfield, Oxford, UK. This support was sponsored by Insmed.

NTM-PD at ECCMID 2021

Non-tuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) infection and NTM pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) are rare diseases and have largely been overlooked in the past. It was welcome to see at the 2021 ECCMID annual congress that NTM and NTM infection/NTM-PD are emerging from the shadows with 3 symposia and more than 20 abstracts directly related to the species identification, diagnosis or treatment of NTM infection and NTM-PD. An overview of the most relevant information presented pertaining to NTM-PD specifically and NTM infection as it might influence our thinking for NTM-PD is provided here and presents an exciting snapshot into emerging scientific and clinical efforts to combat this disease.

For the first time NTM infection and NTM-PD has had a noticeable presence within a highly visible European microbiological congress. A wealth of scientific and clinical research is emerging to tackle the challenges of NTM-PD with the aim, in the future, of improving the clinical outlook for patients.

New recommendations for treating NTM-PD – the 2020 guidelines

In the “Meet The Expert session” ‘Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease – the new ATS/ERS/IDSA/ESCMID guideline’, Dr Jakko van Ingen and Professor Claire Andrejak discussed the content to orient participants on new recommendations and answer questions from the audience.

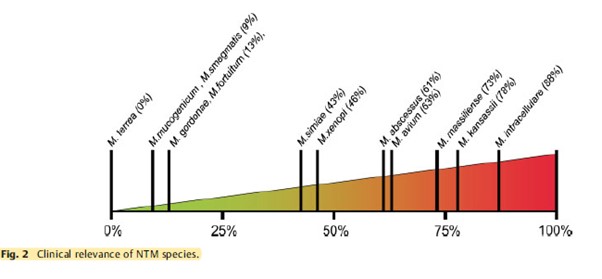

For the first time guidelines for NTM-PD are international providing consistent evidence-based recommendations based on 22 PICO questions with graded evidence of systematic literature review.1 The limitation of the guidelines is the focus only on 4 key mycobacterial species MAC, M. kansasii, M. abscessus, M. xenopi.1 Importantly the guidelines now cover microbiological diagnostics with clear messages to obtain ≥3 respiratory samples each obtained >1 week apart, a recommendation for full speciation of the organism identified so that the clinical virulence of the infecting organisms can be determined, and clear guidelines to undertake susceptibility testing once species are identified. Dr van Ingen recommended to test and report microbiological susceptibility as per CLSI M24/M62 guidelines in broth microdilution and, if not available in regional labs, samples should be sent to reference centres. Diagnostic criteria in 2020 remain unchanged from 20072 and focus on clinical symptoms, radiological evidence and microbiological evidence of 2 positive culture of the same subspecies in order to exclude errors from a single sample.

New recommendations exhort clinicians to start treatment in patients with positive acid-fast bacilli sputum smears as this is suggestive of a high bacterial load, or if there is radiological evidence of cavitary lung disease suggestive of progressive disease.1 Possible reasons to wait to initiate treatment besides mild disease include assessing the readiness of the patient to begin an arduous treatment journey of 12 months or more, understanding of the drug susceptibility of the species identified and potential for recurrent infection.

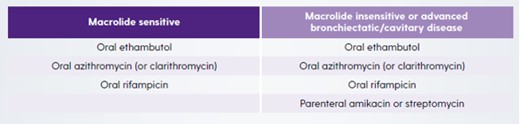

In MAC-PD macrolides form the backbone of treatment and the 2020 guidelines suggest that azithromycin over clarithromycin should be considered, and in the absence of additional clinical data, macrolides plus ethambutol and rifampicin should be used as a 3-drug regimen;1 although Professor Andrejak outlined that studies of 2 drug regimens in MAC-PD are underway (NCT03672630). In patients with severe disease parenteral amikacin or streptomycin should be considered in the early treatment period. For those patients not culture converting by 6 months, the guidelines newly recommend the addition of Amikacin Liposomal Inhalation Suspension (ALIS) based on Phase 3 clinical data from the CONVERT study.1,3

In M. xenopi no correlation between drug susceptibility and clinical outcomes exists and so susceptibility testing is not recommended. With respect to treatment moxifloxacin or clarithromycin can be used and should be included in a treatment regimen of at least 3 drugs.1 Professor Andrejak suggested the possibility to use parenteral amikacin in M. xenopi PD, and an investigator-led study in France to explore the utility of ALIS in M. xenopi is due to start.

In M. kansasii treatment recommendations are to use 3 drug regimens of rifampicin, ethambutol and isoniazid or azithromycin for 12 months; there is no role for aminoglycosides.1 The guideline recommends susceptibility testing at baseline for rifampicin and clarithromycin, particularly given the increase in macrolide resistance. In instances of rifampicin resistance or patients intolerant to rifampicin then fluoroquinolones can be used, but this applies only to M. kansasii and not to other species.1 In patients with mild nodular disease with a macrolide-based regimen a thrice weekly dosing regimen is possible, but all regimens should be dosed for 12 months.

M. abscessus bacterial complex (MABC) -PD is one of the most difficult mycobacterial infections to treat1 but the speakers, both authors of the guidelines noted that current recommendations are relatively weak for this species due to lack of evidence. It was stressed that sub-speciation of M. abscessus is essential as M. abscessus subsp. massiliense is macrolide susceptible whilst M. abscessus subsp. abscessus may be susceptible but prone to inducible resistance. At this time the recommendation is to work closely with an expert centre for NTM-PD and treatment should focus on at least 3 drugs including amikacin, imipenem, macrolides, tigecycline and clofazimine. Use of macrolides depends on susceptibility and should not be used in cases of mutational resistance. The duration of treatment post-culture conversion is as yet unknown and the composition of long-term regimens has not been determined. Dr van Ingen highlighted the need for full clinical trials in M. abscessus rather than case series as are currently available – the medical unmet need in these patients is high and further data on appropriate therapy is needed.

Professor Andrejak counselled that continued monitoring especially microbiological evaluation of sputum every 1–2 months on treatment is essential to determine response to therapy. Similarly, monitoring for adverse events is essential and should focus on liver function tests, audiograms, ECG and so on dependent on the antimicrobials included in the treatment regimen.

Within this session, an overview of new drugs in the pipeline were presented and this demonstrates an unprecedented era of focus and development for NTM-PD. These include minocycline, tedizolid, clofazimine and ALIS that are being evaluated in the laboratory, dynamic models such as hollow fibre models and early human Phase 1/Phase 2 studies.

Meeting the challenges of NTM organisms and NTM-PD

The symposium ‘NTM-PD: do we need to rethink its management’ chaired by Dr van Ingen and Dr Daniela Cirillo (sponsored by Insmed) explored the challenges mycobacterial pulmonary infection present, that requires a new way of thinking for management.

NTM present a particular challenge to treatment because of their cellular physiology including hydrophobic, thick cell walls and their ability to sequester in intracellular spaces including phagocytic cells and biofilms.4–7 Professor Matteo Bassetti presented an overview of sequestration into intracellular spaces and how NTM species, such as M. avium, manipulate normal macrophage processes to reduce phagosome-lysosome fusion, up-regulate genes to facilitate MAC replication and reduce macrophage function so that macrophage apoptosis is controlled enabling effective release of MAC bacteria into the lung environment and infection of neighbouring macrophages so driving a cycle of infection.8–10 Similarly, incorporation of NTM organisms into biofilms presents a physical challenge to the host and to antimicrobial entry and biofilms persist following initiation of phagocyte apoptosis to arrest normal biofilm breakdown mechanisms.11

The problem of the mycobacterial physiology is also coupled with ubiquitous distribution in the environment as presented later in the symposium by Professor Veziris.12,13 NTM-PD is largely initiated by inhalation of organisms in patients with underlying risk factors or may be aspirated from the gastrointestinal tract. Once in the lung NTM can evade antimicrobial action as lung penetration of many systemically administered antibiotics is limited14 requiring high doses to achieve sufficient lung concentrations which may not be possible due to side effects.15 Penetration of many antibiotics into intracellular spaces such as macrophages and biofilms is also poor.14–16

Despite ubiquitous distribution of NTM organisms, exposure does not equate to universal infection. Rather a series of underlying risk factor predispose the tipping point from exposure to infection including underlying lung conditions and some patient morphological characteristics.17 Similarly, diagnosis of NTM-PD or MAC-PD in a patient may not lead to immediate treatment as there are factors of spontaneous culture conversion,18 patient comorbidities and patient wishes to consider.

Aerosolised inhaled antibiotics may address the problem of lung penetration and may reduce selection pressure for multi-drug resistant organisms but is unable to address the issue of macrophage or biofilm penetration providing a rationale for liposomal encapsulation. Liposomes provide an opportunity to penetrate cell membranes, to improve pharmacokinetics of encapsulated antibiotics and potentially reduce systemic toxicity.19 ALIS) licensed in Europe as ARIKAYCE® liposomal 590 mg nebuliser dispersion, is the first inhaled liposome encapsulated antibiotic to be approved and is indicated for use in adult patients with MAC-PD who have limited treatment options and do not have cystic fibrosis, in consideration of official guidance on the appropriate use of antibacterial agents.20 Early studies have demonstrated effective deposition in the lung post-inhalation that persists over 24 hours, and effective penetration in an in vitro study of both MAC infected macrophages and biofilms.21,22

For MAC-PD treatment is lengthy and relies on a macrolide backbone of azithromycin plus ethambutol and rifampicin for at least 6 months to secure culture conversion and then 12 months beyond.1 Professor Veziris presented data to support a new recommendation in the guideline, that of prescribing ALIS to patients with MAC-PD who fail to culture convert by 6 months. A Phase 3 study has demonstrated that using ALIS in patients who have failed oral guideline-based therapy (GBT), many of whom had refractory disease for many years, provides culture conversion in 29% of patients compared with GBT alone 8.9% (p<0.0001);3,23 and it is in these data that guidelines have been revised for patients with MAC-PD (Figure 1).1 Professor Veziris presented further data from ALIS from the long-term follow-up phase of the Phase 3 study which demonstrates that culture conversion is durable while patients are on ALIS plus GBT therapy and is sustained for 3 months or more once all antimicrobial therapy is removed.23

Figure 1. Proportion of patients achieving or maintaining culture conversion

Month 4 was the last time point at which the first of three negative sputum cultures could be achieved for a patient to be considered a convertor at month 6.

GBT, guideline-based therapy.

Emerging technologies and treatments in NTM-PD

The symposium ‘What’s new in mycobacterial disease’, chaired by Professor Florian Maurer and Professor Thomas Schön, explored a range of new developments in NTM-PD and NTM infection. The symposium included two presentations that have the future potential to impact clinical management, one by Dr van Ingen to explore a biomarker to predict treatment success in NTM-PD and one about the potential activity of pentamidine in MAC and M. abscessus from Professor Jelmer Raaijmakers.

Biomarkers in NTM-PD have potential to provide insight into when is the best time to treat patients with disease, the impact of treatment and determining treatment success. Dr van Ingen presented data of a biomarker that can aid prediction of culture conversion in patients once treatment is initiated. Treatment regimens for NTM-PD are often hampered by a limited evidence base and a poor rate of culture conversion despite aggressive treatment.24–26 Time to positivity for MAC organisms in sputum culture was presented as a possible tool to predict patients who will respond to treatment that could be useful in clinical practice and in clinical trials to evaluate new therapies.

The Mycobacterium Growth Indicator Tube (MGIT™) is an automated liquid culture system.27 Using sputa from 49 patients the time to positivity (TTP) in the MGIT system was explored as a biomarker for treatment response. All patients had macrolide-sensitive MAC-PD and TTP was correlated with actual clinical outcomes of conversion, defined as 2 consecutive negative cultures collected ≥4 weeks apart. Mean baseline TTP was higher in patients who culture converted than those who did not (7.68 ± 4.64 vs 4.87 ± 2.20 days, p=0.031), and TTP was also significantly different for patients with nodular-bronchiectatic disease and those with fibrocavitary disease (8.86 ± 5.62 vs 5.29 ± 1.65 days, p=0.010). Differences in TTP increased over time so that, at 3 months, TTP for those converting was 36.38 ± 12.30 days compared with 9.75 ± 5.19 days in non-convertors (p<0.001). These data suggest that MGIT TTP obtained at baseline and at 3 months provides a prediction of culture conversion for MAC-PD. However, Dr van Ingen was keen to outline that time to positivity is predictive of culture conversion only and cannot predict treatment and patient outcomes. However, the use of an early and easily available biomarker that can predict patients who are most likely to convert with therapy can be extremely helpful in planning treatment strategies for individual patients.

New therapies in NTM-PD

Novel treatment approaches were also a focus of NTM abstracts. One by Kan et al.28 suggested that the ligase PafA in the pup-proteosome system (PPS) which is essential for maintaining bacterial persistence in macrophages might provide a potential drug target for patients with persistent intracellular NTM infection. Using proteomic analysis three PafA inhibitors were identified and demonstrated reductions in intracellular mycobacterium in vitro in macrophages. The inhibitors discovered require more investigation but provide an interesting potential adjunct for treating mycobacterial infections such as NTM-PD.

ALIS as a liposomal formulation has been demonstrated in vitro to penetrate macrophages and biofilms where MAC organisms typically sequester to evade host defences and antimicrobial therapy.22 The study by Le Moigne et al.29 explored the ability of ALIS to penetrate phagocytic cells where MABC organisms reside. In this study, access to intracellular mycobacteria was explored using confocal microscopy to observe potential co-localization of ALIS and MABC in cells including epithelial cells and macrophages, and to explore intracellular antimicrobial activity. Confocal microscopy demonstrated that fluorescently tagged ALIS co-localises with MABC within a range of cells, not just phagocytic ones such as macrophages but also epithelial cells, an effect that was not observed with water soluble amikacin. Within cells ALIS demonstrated intracellular bactericidal at concentrations of 32 and 64 μg/mL at 3- and 5-days post-infection. Together, these data suggest that ALIS provides potential in MABC infection with an ability to reach intracellular spaces and have an antimicrobial action on MABC.

M. kansasii pulmonary disease is a common disease-causing mycobacterium second only to MAC and is associated with a poor outlook – with mortality rates up to 50% in patients co-infected with HIV.30 A study by Munoz-Munoz et al.31 explored the susceptibility profile of beta-lactams. Beta-lactam antibiotics are not typically used for mycobacterial infections due to the presence of constitutive beta-lactamases, but in this study beta-lactams in combination with clavulanate did demonstrate potency against the M. kansasii strain ATCC although less than with guideline-based antimicrobial therapy. Amoxicillin/clavulanate was the most active combination (MIC 8 mg/mL) but carbapenems even in the presence of clavulanate had no activity.

Emerging approaches to treating NTM-PD are the development of new molecules or understanding how older molecules can be repurposed. Professor Raaijmakers presented an interesting study exploring the use of pentamidine.32 Pentamidine is most used as an inhaled antibiotic for the treatment of pneumocystis pneumonia and Professor Raaijmakers presented data of pentamidine in isolate models to understand isolate susceptibility, intracellular penetration and efficacy against isolates in phagocytic cells and efficacy against isolates in an ELF model. In vitro time-kill assays of isolates of M. tuberculosis (n=6), M, abscessus (n=3) and M. avium (n=4) demonstrated greatest efficacy of pentamidine against M. tuberculosis at 0.5 MIC, with efficacy against M. avium at 2 x MIC but very limited response against M. abscessus with regrowth observed even at concentration of 32 x MIC.32 In vivo time-kill assay in human blood mononuclear cells (HBMCs) suggested that pentamidine was comparably effective against M. tuberculosis and M. avium with an ability for intracellular penetration but had very limited activity against M. abscessus. In hollow fibre models that emulate the ELF environment pentamidine plus a GBT regimen of azithromycin, ethambutol and rifampicin reduced bacterial density both extracellularly and intracellularly more than GBT alone, but initial reductions provided by pentamidine were not sustained and within 2–3 weeks bacterial densities in both groups were comparable.32

Improving our understanding of the mechanism of infection of MAC

Dr van Ingen’s group presented an abstract33 that explored the interplay between M. avium phagocytosed into human monocytes and clarithromycin. Post-phagocytosis upregulation in genes related to cytokine signalling and immune activation was evident in macrophages whilst within M. avium genes related to nitrate respiration and coding for M. avium antigens were upregulated. These data highlight that the host environment can greatly influence the efficacy of macrolides such as clarithromycin.

Understanding NTM infection and NTM-PD in areas of high TB

Risk factors for NTM-PD such as underlying lung disease are widely recognised, but an abstract from Cruz et al.34 presented the cases of two patients presenting with symptoms that were assumed to be tubercular given the setting of endemic TB in the country. Only on post-mortem of one patient and sputum testing of the other was NTM infection identified. Whilst these cases are in disseminated NTM infection they provide an insight into countries where TB is endemic to continue to keep NTM infection, NTM-PD and NTM testing front of mind.

As with risk factors, the geographical diversity of NTM species is well known.35 a study from Nigeria,36 a country of endemic TB and high HIV, has explored the species variation across 167 participant sputum samples. In this study in patients with HIV enrolled at a national TB clinic the predominating species was M. intracellulare (45.1%), M. interjectum (16.1%) and M. malmoense (12.9%); M. avium was identified in only 6.5% of samples and 12.9% of samples could not be speciated. These data indicate that NTM-PD infection among people infected with HIV is high, which reflects the similar historical perspective of Western countries before the advent of fully accessible high active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART).

A third study by Fraile Torres et al.37 reminds us that in many parts of the world NTM are overtaking TB as an infecting mycobacterial species. In this study 50,728 sputum samples from 15,931 patients were retrospectively examined for NTM over ten years (2010–2020). Of these isolates 3,328 samples from 1,223 patients were positive for NTM. MABC (M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, M. abscessus subsp. Massiliense, and M. abscessus subsp. bolletii ) was the most common infecting organism and among these patients an equal percentage had the underlying risk factors of NCFBE or CF (34.88%), and a small minority had a history of previous TB.

Translating NTM-PD guidelines into routine practice

Understanding drug susceptibility for any infection is important, and 2020 NTM-PD guidelines recommend specific susceptibility testing depending on the predominating infecting NTM species.1 The antimicrobial susceptibility of a range of slow growing mycobacteria were evaluated by Hunkins et al. in the USA.38 In this study of 10,668 isolates (85.2% of which were respiratory; 5 MAC species, 6 other slow growing NTM) it was noted that susceptibility to macrolides, including clarithromycin was high and consistent among species as was susceptibility to rifabutin except for M. asiaticum and M. simiae where susceptibility was approximately 60% or less. Based on the susceptibility breakpoint for IV amikacin, Susceptibility to amikacin was lower at 76.62% for M. avium and 72.44% for M. intracellulare and given the position of IV amikacin in the treatment of MAC suggests that comprehensive antibiograms may be useful to guide therapy for patients.

In a second study,39 the pattern of susceptibility of MAC isolates was explored. Using MALDI-TOF analysis of 737 strains of MAC in sputum M. avium was the most commonly identified single species (n=351, 47.62%) followed M. intracellulare/M. chimaera (combined n=386, 52.37%). Susceptibility against a range of antibiotics recommended by guidelines1 was explored. It was found that susceptibility of M. avium to clarithromycin was maintained in 95.7% of isolates, but only 3% of isolates were susceptible against ethambutol and even lower for IV amikacin. By contrast, susceptibility for these drugs against M. intracellulare/M. chimaera were better.

A cautionary abstract from India40 demonstrated that disease-driving species differ across the world and that drug susceptibility also varies greatly. In this study, the predominant species causing pulmonary disease were MABC, M. fortuitum and, to a limited extent, M. chelonae. Isolates of M. abscessus were susceptible to clarithromycin but only after extended exposure and there were marked decreases in the susceptibility patterns of isolates to imipenem, cefoxitin and fluoroquinolones compared with those reported from other countries. These data suggest that speciation is vital, and in low- or middle-income countries, infection control measures require improvement. The study authors also suggest that NTM-PD guidelines whilst valuable may not always be applicable across all countries.

In summary

At ECCMID 2021 it was clear that NTM-PD as a rare disease is emerging from the shadows with burgeoning research emerging that gives insight into future diagnostics, prognostics and treatment

Βιβλιογραφία:

- Daley CL, et al. Eur Respir J 2020;56:2000535

- Griffith DE, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:367–416.

- Griffith DE, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;198:1559–69.

- Chakraborty P, Kumar A. Microbiol Cell 2019;6:105–22.

- Sousa S, et al. Int J Mycobacteriol 2015;4:36–43.

- Awuh JA, Flo TH. Cell Mol Life Sci 2017;74:1625–48.

- Ganbat D, et al. BMC Pulm Med 2016;16:19.

- Sturgill-Koszycki S, et al. Science 1994;263:678–81.

- Chiplunkar SS, et al. Future Microbiol 2019;14:293–313

- Lee KI, et al. Scientific Reports 2016

- Rose SJ, Bermudez LE. Infect Immun 2014;82:405–12.

- Lee E-S, et al. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2008;18:1207–15

- Nishiuishi Y et al. CID 2007;45:347-351

- Honeybourne D. Thorax 1994;49:104–6

- Wenzler E, et al. Clin Microbiol Rev 2016;29:581–632

- Greendyke R, Byrd TF. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008;52:2019–26

- Prevots DR, Marras TK. Clin Chest Med 2015;36:13–34

- Hwang JA, et al. Eur Repir J 2017;49:1600537.

- Chalmers JD, et al. Eur Respir Rev 2021;30:210010.

- ARIKAYCE liposomal 590 mg nebuliser dispersion. EU Summary of Product Characteristics. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/arikayce-liposomal-product-information_en.pdf [Accessed September 2021]

- Olivier KN, et al. ATS Congress 2016, San Francisco, CA, USA. Poster A3732.

- Zhang J, et al. Front Microbiol 2018;9:915.

- Griffith DE, et al. Chest 2021;160:831–42Apr 19:S0012-3692(21)00703.

- Kwak N, et al. ERJ 2019; 54:1801991

- Zweijpfenning S, et al. Respir Med 2017;131:220–224.

- Griffith DE, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;192:754–60

- Danho R, et al. ECCMID Congress 2021, virtual. Abstract 02527

- Kan HL, et al. ECCMID Congress 2021, virtual. Abstract 00910.

- Le Moigne V, et al. ECCMID Congress 2021, virtual. Abstract 00866.

- Marras TK, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:793–98.

- Munoz-Munoz L, et al. ECCMID Congress 2021, virtual. Abstract 02674

- Raaijmakers J, et al. ECCMID Congress 2021, virtual. Abstract 04116.

- Schildkraut J, et al. ECCMID Congress 2021, virtual. Abstract 03747.

- Cruz MG, et al. ECCMID Congress 2021, virtual. Abstract 00169.

- Hoefsloot W, et al. Eur Respir J 2013;42:1604–13.

- Olayinka A, et al. ECCMID Congress 2021, virtual. Abstract 00942.

- Fraile Torres AM, et al. ECCMID Congress 2021, virtual. Abstract 04043.

- Hunkins J, et al. ECCMID Congress 2021, virtual. Abstract 02793.

- Fernandez-Pittol M, et al. ECCMID Congress 2021, virtual. Abstract 02394.

- Irfana M, et al. ECCMID Congress 2021, virtual. Abstract 02548.

![]()

Medical writing and editorial support was provided by Highfield, Oxford, UK. This support was sponsored by Insmed.

Κατανοώντας τους παράγοντες κινδύνου για NTM-PD

Οι κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες ERS/ATS/ESCMID/IDSA για τη NTM-PD 2020 παρουσιάζουν πώς γίνεται η διάγνωση ενός ασθενή με NTM-PD, με βάση τις αξιολογήσεις των κλινικών, απεικονιστικών και μικροβιολογικών δεδομένων (Daley 2020). Ωστόσο, όταν ένας ασθενής επισκέπτεται το νοσοκομείο, τι ακριβώς επάνω του θα παρακινήσει τον κλινικό ιατρό να σκεφτεί τη διεξαγωγή εξετάσεων για NTM;

Αν κατανοήσουμε τους παράγοντες κινδύνου που εμφανίζονται συνήθως στους ασθενείς με NTM-PD, θα έχουμε μια πολύτιμη πληρέστερη εικόνα για τον ασθενή που πιθανώς να επωφεληθεί από τις εξετάσεις για NTM, είτε γιατί θα αποκλειστεί η πιθανότητα της νόσου είτε, στην περίπτωση που όντως υπάρχει λοίμωξη από NTM, γιατί θα καθοριστεί το κατάλληλο σχέδιο δράσης. Στους παράγοντες κινδύνου για νόσηση από NTM-PD περιλαμβάνονται ενδογενείς παράγοντες που σχετίζονται αποκλειστικά με τον ίδιο τον ασθενή (παράγοντες κινδύνου του ξενιστή), περιβαλλοντικοί παράγοντες κινδύνου (έκθεση), ανοσολογικοί παράγοντες κινδύνου, γενετικοί παράγοντες κινδύνου, καθώς και η παρουσία υποκείμενων πνευμονικών παθήσεων ή νοσημάτων (Cowman 2019).

|

Παράγοντες που αυξάνουν την ευαισθησία για NTM-PDΠαράγοντες |

Αυξημένος κίνδυνος ή επιπολασμός της λοίμωξης* |

|

Βρογχεκτασία |

44–187,5 (Prevots 2015, Andrejak 2013) |

|

Πρωθύστερη φυματίωση |

69,0–178,3 (Axon 2019, Andrejak 2013) |

|

Χαμηλός δείκτης BMI |

9,1 (Prevots 2015) |

|

Κυστική ίνωση |

6,6–13,0 (Olivier 2003, Roux 2009) |

|

ΧΑΠ (με λήψη εισπνεόμενων κορτικοστεροειδών) |

29,1 (Andrejak 2013) |

|

ΧΑΠ (χωρίς εισπνεόμενα κορτικοστεροειδή) |

2,0–10,0 (Prevots 2015) |

|

Παραμορφώσεις του θώρακα |

5,4 (Prevots 2015) |

|

Καρκίνος του πνεύμονα |

3,4 (Prevots 2015) |

|

Άσθμα |

2,0–7,8 (Hojo 2012, Andrejak 2013) |

|

Χρήση κορτικοστεροειδών |

1,6–8,0 (Prevots 2015) |

|

ΓΟΠ |

1,5–5,3 (Prevots 2015) |

|

Ρευματοειδής αρθρίτιδα |

1,5–1,9 (Prevots 2015) |

|

Ανοσορυθμιστική/ ανοσοκατασταλτική αγωγή |

1,3–2,2 (Prevots 2015) |

*Λόγος συμπληρωματικών πιθανοτήτων (odds ratio ή OR), σχετικός κίνδυνος ή σχετικός επιπολασμός

Οι παράγοντες που αυξάνουν τον κίνδυνο νόσησης από NTM-PD θα πρέπει να συνυπολογίζονται κατά τη λήψη της απόφασης για το ποιοι ασθενείς θα ελεγχθούν προληπτικά ή θα υποβληθούν σε εξετάσεις για την παρουσία λοίμωξης.

Υποκείμενες πνευμονικές παθήσεις

Βρογχεκτασία

Όπως είναι γνωστό, η βρογχεκτασία συνιστά παράγοντα κινδύνου για τη NTM-PD, αλλά η εκτίμηση της διαβάθμισης του κινδύνου ποικίλλει4,9,10. Η λοίμωξη από τα NTM μπορεί να προκαλέσει βρογχεκτασία, ενώ στους ασθενείς με προϋπάρχουσα βρογχεκτασία μπορεί να διευκολύνει την προοδευτική εξέλιξη της νόσου, καθώς οι βρόγχοι με ανατομικές αλλοιώσεις είναι ευπαθείς σε λοιμώξεις 11. Για τους ασθενείς με βρογχεκτασία, εκτιμάται ότι ο κίνδυνος να νοσήσουν από NTM-PD είναι κατά 44 έως 187,5 φορές μεγαλύτερος3,4, ενώ ο επιπολασμός της NTM-PD μεταξύ των ασθενών με βρογχεκτασία εκτιμήθηκε περίπου στο 9,3%.12

Η βρογχεκτασία συσχετίζεται με τη NTM-PD σε γυναίκες ασθενείς, με χαμηλή μάζα λίπους, ακόμα και μετά τις ρυθμίσεις για τον δείκτη BMI, την ηλικία και τον δείκτη μάζας λίπους.13 Μελέτη στις ΗΠΑ αποπειράθηκε να προβλέψει ποιοι ασθενείς με βρογχεκτασία ενδέχεται να νοσούν επίσης από NTM-PD.14 Στη συγκεκριμένη μελέτη, τα αποτελέσματα υπέδειξαν ότι σε περισσότερα από δύο αιτήματα καταβολής αποζημίωσης, τα οποία κατατέθηκαν σε ασφαλιστή υγείας στη διάρκεια 12 μηνών και με 30 ημέρες χρονική απόσταση μεταξύ τους, αναφερόταν η διάγνωση πνευμονικής λοίμωξης από NTM σε ασθενείς που είχαν επίσης βρογχεκτασία. Ωστόσο, οι συντάκτες της μελέτης σημείωναν ότι η ευαισθησία πρόβλεψης είναι χαμηλή και, συνεπώς, η πραγματική συχνότητα εμφάνισης μπορεί να έχει υποτιμηθεί σημαντικά. Επιπλέον, μια πρόσφατη μελέτη11 κατέδειξε ότι, παρόλο που η NTM-PD στους ασθενείς με βρογχεκτασία συνδέεται με απεικονιστικές μεταβολές και επιδεινούμενα συμπτώματα, και πάλι η Βαθμολογία Βαρύτητας Βρογχεκτασιών (BSI) μπορεί να παραμείνει αμετάβλητη. Κατά συνέπεια, για τους ασθενείς με βρογχεκτασία, ιδίως εκείνους με απεικονιστικές μεταβολές, συνιστάται ο έλεγχος δείγματος πτυέλων για NTM. Παρομοίως, οι κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες ERS και BTS15,16 υποδεικνύουν ότι θα πρέπει να διερευνάται η πιθανότητα νόσησης από NTM-PD για όλους τους ασθενείς με βρογχεκτασία οι οποίοι λαμβάνουν ήδη μονοθεραπεία με μακρολίδια ή είναι υποψήφιοι λήπτες.

|

Σημαντική επισήμανση: Οι ασθενείς με βρογχεκτασία έχουν αυξημένο κίνδυνο νόσησης από NTM-PD, ο οποίος είναι από 44 έως 187,5 φορές μεγαλύτερος απ’ ό,τι για εκείνους χωρίς βρογχεκτασία 3,4 |

Κυστική ίνωση

Η NTM-PD εμφανίζεται όλο και πιο συχνά σε ασθενείς με κυστική ίνωση, σε παγκόσμιο επίπεδο. Οι λόγοι παραμένουν άγνωστοι, αλλά ίσως να σχετίζονται με τη μεγαλύτερη διάρκεια ζωής των ασθενών, την πρόοδο που έχει σημειωθεί στον έλεγχο των βακτηριακών λοιμώξεων, όπως στην περίπτωση του Pseudomonas aeruginosa, καθώς και τη μεγαλύτερη επαγρύπνηση που οδηγεί σε αυξανόμενες διαγνώσεις NTM-PD7,17. Σύμφωνα με τις τρέχουσες εκτιμήσεις μιας μελέτης, τα NTM προκαλούν λοίμωξη στο 32% των ασθενών με κυστική ίνωση.18 Ο κίνδυνος νόσησης από NTM-PD για τους ασθενείς με κυστική ίνωση είναι υψηλός και ο επιπολασμός της λοίμωξης στον συγκεκριμένο πληθυσμό αυξημένος, μεγαλύτερος κατά 6,6 έως και 13 φορές.6,7

Μια μετα-ανάλυση απέδειξε ότι οι ασθενείς με κυστική ίνωση έχουν σημαντικά μεγαλύτερη πιθανότητα να είναι θετικοί σε καλλιέργειες για NTM αν είναι μεγαλύτερης ηλικίας (p<0,01), έχουν αποικισμό από Aspergillus fumigatus (OR 3,59 p<0,001), Staphylococcus aureus (OR 1,66 p=0,001) ή Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (OR 3,41 p<0,01), ή λαμβάνουν εισπνεόμενα κορτικοστεροειδή (OR 1,98 p<0,01). Καμία άλλη παράμετρος δεν έδειξε σημαντική συσχέτιση19. Λαμβάνοντας υπόψη όλα τα δεδομένα, οι ασθενείς με κυστική ίνωση, καθώς και σοβαρές παθήσεις ή λοιμώξεις, θα πρέπει να παρακολουθούνται στενά για NTM-PD.

|

Σημαντική επισήμανση: Στην περίπτωση της κυστικής ίνωσης, ο κίνδυνος νόσησης από NTM-PD είναι αυξημένος, με τα ποσοστά της NTM-PD στους ασθενείς με κυστική ίνωση να είναι έως και 13 φορές υψηλότερα απ’ ό,τι στον γενικό πληθυσμό (Olivier 2003), ιδίως σε ασθενείς μεγαλύτερης ηλικίας και σε αυτούς με αποικισμό από βακτήρια ή σε αγωγή με εισπνεόμενα κορτικοστεροειδή19 |

ΧΑΠ

Η ΧΑΠ είναι μια συνήθης συννοσηρότητα της NTM-PD και μια μελέτη προγνωστικής μοντελοποίησης 20 υπέδειξε ότι συνιστά έναν από τους υψηλότερους μεμονωμένους προγνωστικούς δείκτες για τη NTM-PD. Στις ΗΠΑ, τα ποσοστά περιστατικών NTM-PD σε ασθενείς με ΧΑΠ αυξάνονται συνεχώς από το 2012 21 και, μάλιστα, υπερδιπλασιάστηκαν στο διάστημα από το 2011 έως το 2015 (σε σύγκριση με αύξησή τους κατά ένα τέταρτο στο διάστημα από το 2001 έως το 2005). Ο κίνδυνος θνητότητας για ασθενείς με ΧΑΠ και λοίμωξη από ΝΤΜ είναι μεγαλύτερος κατά 1,43 φορές απ’ ό,τι για τους ασθενείς με ΧΑΠ που δεν νοσούν από NTM-PD 21, ενώ καναδική μελέτη υπέδειξε ότι το OR για τη ΧΑΠ συνιστά παράγοντα κινδύνου της τάξης του 15,7.4

Μικρότερης εμβέλειας μελέτη κατέδειξε ότι, εφόσον δεν ληφθούν υπόψη ο δείκτης BMI, ο βιαίως εκπνεόμενος όγκος (FEV1) και η χρήση εισπνεόμενων κορτικοστεροειδών, τα ποσοστά της NTM-PD στους ασθενείς με ΧΑΠ είναι υψηλότερα απ’ ό,τι στον γενικό πληθυσμό.22 Παρομοίως, ο λόγος επικινδυνότητας (hazard ratio, HR) για τη NTM-PD στους ασθενείς με προϋπάρχουσα ΧΑΠ ήταν 9,15 μετά από προσαρμογή για το φύλο και την ηλικία και έπεσε μόλις στο 6,01 ακόμα και μετά από πλήρη προσαρμογή για όλους τους παράγοντες.23 Τα δεδομένα αυτά είναι σημαντικά, καθώς η μελέτη του Marras κ.ά. διεξήχθη σε πληθυσμό άνω των έξι εκατ. ατόμων και η συσχέτιση της NTM-PD ως υποκείμενης συννοσηρότητας με τη ΧΑΠ διερευνήθηκε αναλυτικά.

Αν λάβουμε υπόψη τη σταθερή αύξηση των συνολικών ποσοστών της ΧΑΠ, καθώς και τον κίνδυνο νόσησης από NTM-PD για τους ασθενείς με ΧΑΠ, μεταβολές στα συμπτώματα ή απεικονιστικές μεταβολές θα πρέπει να διερευνώνται περαιτέρω με τη λοίμωξη από NTM να είναι ένα από τα πρώτα ενδεχόμενα που θα πρέπει να εξετάζονται.

|

Σημαντική επισήμανση: Όταν παραβλέπονται άλλοι παράγοντες κινδύνου όπως ο δείκτης BMI, η πνευμονική λειτουργία και η χρήση εισπνεόμενων κορτικοστεροειδών, η ΧΑΠ συνεχίζει να συνιστά παράγοντα αυξημένου κινδύνου – έως και 15,7 φορές μεγαλύτερου – για λοίμωξη από NTM3,22,23 |

Άσθμα

Είναι γνωστό ότι οι ασθενείς που λαμβάνουν εισπνεόμενα κορτικοστεροειδή (ICS) έχουν αυξημένο κίνδυνο λοίμωξης από NTM.4,24 Σύμφωνα με μια μελέτη, σε συνδυασμό με το άσθμα per se, ο κίνδυνος για NTM-PD αυξάνεται κατά 7,8 φορές περισσότερο4. Σε μελέτη ασθενών-μαρτύρων από τον ίδιο πληθυσμό διερευνήθηκε συγκεκριμένα η σύνδεση μεταξύ άσθματος και λοίμωξης από NTM και υποδείχτηκε ότι οι ασθενείς με άσθμα είναι μεγαλύτερης ηλικίας, παρουσιάζουν σοβαρό περιορισμό της ροής αέρα και λαμβάνουν εισπνεόμενα κορτικοστεροειδή για μεγαλύτερα χρονικά διαστήματα (>5 έτη) και σε υψηλότερες δόσεις (Hojo 2012). Οι συντάκτες επεσήμαναν ότι η λήψη ICS από τους συγκεκριμένους ασθενείς μπορεί να είναι όντως παράγοντας κινδύνου που συμβάλλει στη λοίμωξη. Λαμβάνοντας υπόψη όλα τα δεδομένα, το άσθμα με τη χαρακτηριστική φλεγμονή και απόφραξη των αεραγωγών είναι λογικό να αποτελεί έναν ανεξάρτητο παράγοντα κινδύνου για τη NTM-PD τον οποίο πιθανώς να ενισχύει ακόμα περισσότερο η χρήση των εισπνεόμενων κορτικοστεροειδών.

|

Σημαντική επισήμανση: Το άσθμα αυξάνει τον κίνδυνο νόσησης από NTM-PD έως και 7,8 φορές περισσότερο4.

|

ς παθή

σεις

Ανοσοκατεσταλμένοι ασθενείς

Είναι γνωστό εδώ και καιρό ότι η χρήση εισπνεόμενων κορτικοστεροειδών αυξάνει τον κίνδυνο για πνευμονία.25 Μελέτη σε ασθενείς άνω των 60 ετών, με άσθμα, ΧΑΠ ή σύνδρομο αλληλεπικάλυψης ΧΑΠ - άσθματος, αξιολόγησε και συνέκρινε τις επιπτώσεις από τη χρήση ή όχι εισπνεόμενων κορτικοστεροειδών σε εκείνους με NTM-PD. Η υφιστάμενη χρήση εισπνεόμενων κορτικοστεροειδών σχετίστηκε με αυξημένο λόγο OR για NTM-PD ίσο με 1,86, με στατιστικώς σημαντική αύξηση στην περίπτωση της φλουτικαζόνης (OR 2,09) έναντι της βουδεσονίδης (OR 1,19), ενώ η σχέση μεταξύ νόσου και λήψης ICS ήταν δοσοεξαρτώμενη.24

Στη ρευματοειδή αρθρίτιδα (RA), η λήψη βιολογικών παραγόντων όπως αυτών που στοχεύουν σε παράγοντες νέκρωσης όγκων (αντι-TNF παράγοντες) σχετίζεται με αυξημένο κίνδυνο νόσησης από NTM-PD 26, ο οποίος προσεγγίζει τα ανώτατα επίπεδα στην περίπτωση της αδαλιμουμάμπης έναντι της ινφλιξιμάβης και ετανερσέπτης: οι ασθενείς που λαμβάνουν τη συγκεκριμένη αγωγή είναι σε 5–10 φορές μεγαλύτερο κίνδυνο απ' ό,τι οι ασθενείς με ρευματοειδή αρθρίτιδα που δεν εκτίθενται σε αγωγή αντι-TNF ή ο γενικός πληθυσμός.26,27 Παρομοίως, σε ασθενείς στη Νότια Κορέα στους οποίους χορηγούταν αγωγή αντι-TNF, αναφέρθηκε υψηλότερη συχνότητα εμφάνισης της NTM-PD με 230 περιστατικά ανά 100.000 ασθενείς,27 ,ενώ στις ΗΠΑ και τη Νότια Κορέα το 70–100% των ασθενών με ρευματοειδή αρθρίτιδα και υποκείμενο πνευμονικό νόσημα είχε NTM-PD, γεγονός που υποδεικνύει συσσώρευση του κινδύνου 27. Ο Prevots κ.ά. εκτιμούν ότι ο αυξημένος κίνδυνος για νόσηση από NTM-PD για τους ασθενείς σε ανοσορυθμιστική ή ανοσοκατασταλτική αγωγή είναι συνολικά από 1,3 έως 2,2 φορές μεγαλύτερος.3

Κι άλλοι βιολογικοί παράγοντες όπως η ριτουξιμάμπη (η οποία χρησιμοποιείται, μεταξύ άλλων, για τον καρκίνο και τη ρευματοειδή αρθρίτιδα), η αμπατασέπτη, η τοσιλιζουμάμπη και η ουστεκινουμάμπη ενέχουν θεωρητικά αυξημένο κίνδυνο νόσησης από NTM-PD, αλλά στην παρούσα περίοδο δεν υπάρχουν διαθέσιμες έρευνες και τα δεδομένα προέρχονται αποκλειστικά από περιορισμένη σειρά περιστατικών.27 Παρομοίως, ασθενείς λήπτες μοσχεύματος που λάμβαναν ανοσοκατασταλτικά φάρμακα, όπως το tacrolimus, διαγνώστηκαν με NTM-PD, αλλά τα δεδομένα προέρχονται και πάλι από περιορισμένη σειρά περιστατικών ή αναφορές μεμονωμένων περιστατικών.28,29

Αν και συμβαίνει πλέον σπάνια, είχε παρατηρηθεί αύξηση των περιστατικών NTM-PD πρωτίστως σε άτομα με HIV/AIDS λόγω της ανοσοκατεσταλμένης κατάστασής τους.27 Με την έλευση της αντιρετροϊκής αγωγής υψηλής δραστικότητας (HAART) υπήρξε κατακόρυφη πτώση των περιστατικών NTM-PD και πλέον η διάγνωση της νόσου μεταξύ των ατόμων που ζουν με τον ιό HIV σπανίζει.

Ασθενείς που λαμβάνουν ανοσοκατασταλτική αγωγή, ιδίως εκείνοι με υποκείμενο πνευμονικό νόσημα, θα πρέπει να ελέγχονται προληπτικά όταν υφίσταται κλινική υποψία. Επίσης, είναι εξαιρετικά σημαντικό συνάδελφοι ρευματολόγοι ή χειρουργοί με εξειδίκευση στις μεταμοσχεύσεις να αντιλαμβάνονται τον θεωρητικό κίνδυνο της ανοσοκατασταλτικής αγωγής σε σχέση με τη NTM-PD, ώστε να μπορούν να παραπέμψουν τον ασθενή κατάλληλα και εγκαίρως.

|

Σημαντική επισήμανση: Σε γενικές γραμμές, στην περίπτωση λήψης ανοσορυθμιστικής ή ανοσοκατασταλτικής αγωγής, ο κίνδυνος για νόσηση από NTM-PD αυξάνεται από 1,5 έως 2,2 φορές περισσότερο.3 |

Παράγοντες κινδύνου του ξενιστή: μορφολογία του ασθενή

Τα χαρακτηριστικά που συνιστούν προδιαθεσιακούς παράγοντες κινδύνου για τη NTM-PD είναι ευρέως γνωστά και περιλαμβάνουν τα ακόλουθα:30

- Βιολογικό φύλο – οι γυναίκες διατρέχουν μεγαλύτερο κίνδυνο

- Παραμορφώσεις του θώρακα όπως, μεταξύ άλλων, σκαφοειδές στέρνο και σκολίωση

- Μεγαλύτερο ύψος από τον μέσο όρο (>165 cm για τις γυναίκες)

- Χαμηλός δείκτης BMI (<20 kg/m2)

- Χαμηλότερο ποσοστό λίπους και κατώτερες μετρήσεις περιφέρειας μηρού σε σύγκριση με τους ασθενείς χωρίς λοίμωξη από NTM.

Τα συγκεκριμένα μορφολογικά χαρακτηριστικά περιγράφηκαν αρχικά ως «σύνδρομο της Λαίδης Γουίντερμιρ», από τον χαρακτήρα του θεατρικού έργου του Όσκαρ Ουάιλντ Η βεντάλια της λαίδης Γουίντερμιρ 31. Ωστόσο, θα πρέπει να σημειωθεί ότι και στους άνδρες, παρόμοια μορφολογικά χαρακτηριστικά σχετίζονται επίσης με αυξημένο κίνδυνο για νόσηση από NTM-PD και ονομάζονται αντιστοίχως «σύνδρομο του λόρδου Γουίντερμιρ».32

Η μορφολογία του ασθενή μπορεί επίσης να επηρεάσει την πορεία της NTM-PD μετά τη διάγνωση, με τους ασθενείς που έχουν χαμηλά ποσοστά κοιλιακού λίπους να διατρέχουν αυξημένο κίνδυνο προοδευτικής εξέλιξης της νόσου.33 Μελέτη ασθενών-μαρτύρων υπέδειξε ότι ασθενείς με ύψος άνω του μέσου όρου και παραμορφώσεις του θώρακα έχουν αυξημένο λόγο συμπληρωματικών πιθανοτήτων (OR) για NTM-PD της τάξης του 1,1 και 5,4 αντίστοιχα, ενώ αποδείχτηκε ότι ένας δείκτης BMI άνω του φυσιολογικού (>26 kg/m2) δρα προστατευτικά έναντι της NTM-PD (OR 0,11)34. Παρομοίως, ο χαμηλός δείκτης BMI σχετίστηκε με αυξημένο κίνδυνο νόσησης από NTM-PD κατά 9,1 φορές περισσότερο.3 Μελέτες οικογενείας υπέδειξαν συρροή περιστατικών NTM-PD μεταξύ συγγενών ασθενών με τα εν λόγω «επικίνδυνα» μορφολογικά χαρακτηριστικά, γεγονός που υποδεικνύει ότι υπάρχει μια υποβόσκουσα γονιδιακή συσχέτιση3,35.

|

Σημαντική επισήμανση: Ορισμένα μορφολογικά χαρακτηριστικά σχετίζονται με αυξημένο κίνδυνο νόσησης από NTM-PD, καθώς το μεγάλο ύψος αυξάνει τον κίνδυνο κατά 1,1 φορές περισσότερο, οι παραμορφώσεις του θώρακα κατά 5,4 φορές περισσότερο και ο χαμηλός δείκτης BMI κατά 9,1 φορές περισσότερο3,34 |

Γενετική προδιάθεση

Ο αυξημένος κίνδυνος νόσησης από NTM-PD σχετίζεται με διάφορες γενετικά κληρονομικές νόσους, στις οποίες περιλαμβάνονται η κυστική ίνωση, όπως επισημάνθηκε παραπάνω, η ανεπάρκεια α1-αντιτρυψίνης (AAT) και η πρωτοπαθής δυσκινησία των κροσσών (ΠΔΚ). Τόσο στην ΑΑΤ όσο και στην ΠΔΚ, η προδιάθεση για τη NTM-PD οφείλεται στον αντίκτυπο της νόσου στον πνεύμονα. Στην AAT, η εμφάνιση της ΧΑΠ είναι ιδιαίτερα συχνό φαινόμενο μετά την ηλικία των 30 ετών36. Στην ΠΔΚ, οι γονιδιακές μεταλλάξεις οδηγούν σε υποβαθμισμένη και ασυντόνιστη λειτουργία των κροσσών στον πνεύμονα, με αποτέλεσμα την πρόκληση βρογχεκτασίας: ο επιπολασμός της NTM-PD στους ασθενείς με ΠΔΚ εκτιμάται ότι ανέρχεται σε ποσοστό περίπου 15%37. Οι ασθενείς με ΠΔΚ θα πρέπει να υποβάλλονται σε προληπτικό έλεγχο για NTM-PD, όπως ακριβώς για την κυστική ίνωση, και συνιστάται τακτική καλλιέργεια πτυέλων κάθε 3–6 μήνες37. Παρομοίως, τόσο στην περίπτωση της κυστικής ίνωσης όσο και της ΠΔΚ, η εκπαίδευση των ασθενών πάνω στην αποτελεσματική κάθαρση των αεραγωγών έχει ζωτική σημασία, καθώς ο καθαρισμός του πνεύμονα προλαμβάνει τη λοίμωξη και, αν ο ασθενής έχει διαγνωστεί με NTM-PD, την πρόκληση βλάβης στον πνεύμονα.

Τα σύνδρομα που συνιστούν πρωτοπαθείς ανοσοανεπάρκειες, όπως η κληρονομική ευαισθησία σε μυκοβακτηριακές λοιμώξεις (MSMD), μια σπάνια πάθηση, αποτελούν παράγοντα κινδύνου νόσησης από NTM-PD. Η MSMD σχετίζεται με διαταραχές του υποδοχέα ιντερλευκίνης και μεταλλάξεις γονιδίων που συμμετέχουν στη φλεγμονώδη απόκριση 38. Παρομοίως, ποικίλες γενετικές διαταραχές στη φλεγμονώδη οδό όπως η ιντερλευκίνη (IL-12) της ιντερφερόνης-γ (IFNγ) και οι υποδοχείς IFN/IL, καθώς και πρωτεΐνες μακροφάγων όπως το γονίδιο NRAMP1 (πρωτεΐνη μακροφάγων που σχετίζεται με τη φυσική αντίσταση 1), είναι γνωστοί παράγοντες κινδύνου νόσησης από NTM-PD39, υποδεικνύοντας πιθανότατα μια συσχέτιση φλεγμονώδους αντίδρασης και νόσου.

Πρωθύστερη ή υφιστάμενη φυματίωση

Σε πρόσφατη μελέτη40 στην Κίνα, μια αξιολόγηση των περιστατικών NTM-PD σε ασθενείς με φυματίωση υπέδειξε ότι ένας στους δεκαπέντε έχει επίσης λοίμωξη από NTM. Τα συνηθέστερα λοιμογόνα είδη ήταν το M. intracellulare και το M. abscessus. Ένα παρεμφερές περιστατικό συλλοίμωξης παρουσιάστηκε μερικά χρόνια πριν, με τους συντάκτες της μελέτης να υποδεικνύουν ότι η λοίμωξη από το μυκοβακτηρίδιο της φυματίωσης προκαλείται στην πλειονότητα των ασθενών στους πρώτους έξι μήνες από τη διάγνωση της NTM-PD και ότι είναι κατά πολύ συχνότερη σε άτομα με ιστορικό πρωθύστερης NTM-PD41. Αντιστρόφως, όπως υποδείχτηκε, στο ΗΒ η πρωθύστερη φυματίωση ως παράγοντας κινδύνου για τη NTM-PD επιφέρει λόγο OR της τάξης του 69,0, ενώ στη Δανία υπήρξε υπερδιπλασιασμός του κινδύνου με OR της τάξης του 178,34,42.

Παρόλο που η φυματίωση φαίνεται να υποχωρεί στην Ευρώπη 43, συνεχίζει να είναι ενδημική σε ορισμένες χώρες και η άνοδος των περιστατικών φυματίωσης ανθεκτικής στη ριφαμπικίνη και σε πολυφαρμακευτικά σχήματα θεραπείας σημαίνει ότι η νόσος παραμένει μια σημαντική παράμετρος που θα πρέπει να λαμβάνεται υπόψη. Όταν παρουσιάζεται ένας ασθενής με συμπτώματα NTM-PD και γεννάται η υποψία λοίμωξης, οι ασθενείς θα πρέπει να υποβάλλονται πάντα σε προληπτικό έλεγχο για πρωθύστερη φυματίωση.

Γαστροοισοφαγική παλινδρόμηση (ΓΟΠ)

Στους υπόλοιπους προδιαθεσιακούς παράγοντες κινδύνου περιλαμβάνεται η ΓΟΠ44 με αυξημένο κίνδυνο που εκτιμάται να είναι κατά 1,5–5,3 φορές μεγαλύτερος.3 Οι ασθενείς με ΓΟΠ είναι πιθανότερο να έχουν θετική οξεάντοχη χρώση των βακτηρίων ΝΤΜ και να νοσούν από NTM-PD σε σύγκριση με τους ασθενείς χωρίς ΓΟΠ. Παρομοίως, στους ασθενείς με πνευμονική νόσο από MAC (MAC-PD), εμφανίζεται ένα υψηλό ποσοστό περιστατικών με τη ΓΟΠ ως συννοσηρότητα 44,45. H ΓΟΠ εμφανίζεται συχνότερα σε ασθενείς με NTM-PD με παρουσία οζιδίων σε ποσοστό περίπου 26%45, ακόμα κι αν γίνει προσαρμογή για άλλους παράγοντες όπως η ηλικία, το φύλο, ο δείκτης BMI και οι εξετάσεις πνευμονικής λειτουργίας. Ασθενείς με ΓΟΠ και NTM-PD που λαμβάνουν οξεοκατασταλτικά φάρμακα είναι πιθανότερο να έχουν εμφάνιση πύκνωσης και οζίδια με μέγεθος άνω των 5 mm.44 Η ΓΟΠ πιθανώς να συνιστά παράγοντα κινδύνου λόγω της αναρρόφησης βακτηρίων της χολής από τον πνεύμονα και θεωρείται ότι η καταστολή οξέος υποστηρίζει τον πολλαπλασιασμό και την επιβίωση των βακτηρίων στη χολή.44

Περιβαλλοντική έκθεση

Τα NTM είναι πανταχού παρόντα στο περιβάλλον, απαντώνται τόσο στο έδαφος όσο και στο νερό 46–48 και έχει εκφραστεί η άποψη ότι το περιβάλλον αποτελεί τη «δεξαμενή» των συγκεκριμένων βακτηρίων που προκαλούν λοίμωξη στον ανθρώπινο οργανισμό. Ο αυξανόμενος επιπολασμός της NTM-PD έχει σχετιστεί με τα αυξημένα επίπεδα υδρατμών στην ατμόσφαιρα 49 και η παρουσία NTM στο νερό οικιακής χρήσης αναφέρεται συχνότερα για τους ασθενείς με NTM-PD απ’ ό,τι για τους μη νοσούντες50, αυξάνοντας τον κίνδυνο νόσησης από NTM-PD έως και 5,9 φορές περισσότερο3. Τα NTM είναι επίσης παρόντα και σε ένα πλήθος άλλα κλινικά περιστατικά που σχετίζονται με το εξωτερικό και το οικιακό περιβάλλον, αλλά ο ρόλος τους στη λοίμωξη παραμένει ασαφής2. Με δεδομένη τη διεισδυτική φύση των ΝΤΜ, ο περιορισμός της λοίμωξης είναι δύσκολος, αλλά απλά μέτρα προφύλαξης όπως η τακτική αντικατάσταση των φίλτρων νερού, η αποφυγή λουτρών υδρομασάζ, ο τακτικός καθαρισμός της κεφαλής ντους και η χρήση γαντιών κατά τις κηπουρικές εργασίες μπορούν να βοηθήσουν τους ασθενείς σε κίνδυνο.

Συνοπτικά

Από τις όλο και περισσότερες έρευνες σε εξέλιξη, καθίσταται σαφές ότι υπάρχει μια σειρά δυνητικών παραγόντων κινδύνου που μπορούν να εγείρουν την κλινική υποψία για NTM-PD. Ωστόσο, είναι γνωστό ότι ούτε κάθε ψηλή, λεπτή γυναίκα ούτε κάθε ασθενής με ΓΟΠ, αν και με αυξημένο παράγοντα κινδύνου για NTM-PD, θα νοσήσει και, συνεπώς, η περαιτέρω διερεύνηση με βάση την κλινική υποψία έχει θεμελιώδη σημασία. Στο πλαίσιο αυτό, μεταξύ άλλων, θα πρέπει να λαμβάνονται υπόψη μεταβολές ή επιδείνωση στην κλινική κατάσταση του ασθενή με υψηλό κίνδυνο για NTM-PD και να μελετάται το ιατρικό και κοινωνικό ιστορικό, προκειμένου να γίνονται αντιληπτοί οι ιατρογενείς κίνδυνοι στη ζωή του ασθενή. Στη συνέχεια, η διεξαγωγή εξετάσεων και η παρακολούθηση του ασθενή, όταν υφίσταται υποψία για νόσηση από NTM-PD, έχει επιτακτική σημασία.

|

Σημαντική επισήμανση: Διεξάγετε εξετάσεις και παρακολουθείτε τους ασθενείς με δυνητικά κλινικά συμπτώματα ή επιδεινούμενα κλινικά συμπτώματα οι οποίοι ταιριάζουν με το προφίλ της νόσου NTM-PD: · Ψηλοί, λεπτοί άντρες ή γυναίκες · Ασθενείς με υποκείμενες πνευμονικές παθήσεις: άσθμα, βρογχεκτασία και ΧΑΠ · Ασθενείς με γενετικά κληρονομικές παθήσεις: κυστική ίνωση, ΑΑΤ, ΠΔΚ · Ασθενείς με ΓΟΠ ή περιβαλλοντική έκθεση |

Τι πρέπει να κάνετε; Διερευνήστε την πιθανή ύπαρξη ΝΤΜ για τους ασθενείς με παράγοντες κινδύνου, ώστε να διαγνώσετε εγκαίρως τη λοίμωξη, και ακολουθήστε τις τρέχουσες κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες (Daley 2020) για την έναρξη της θεραπείας, προκειμένου να προληφθεί η προοδευτική εξέλιξη της νόσου και να επιτευχθεί η αρνητικοποίηση της καλλιέργειας. Σκέψου τα NTM! Κάνε εξετάσεις για NTM!

Βιβλιογραφία:

1. Daley CL, et al. Eur Respir J 2020;56:2000535.

2. Cowman S, et al. Eur Respir J 2019;54:1900250.

3. Prevots DR, et al. Clin Chest Med 2015;36:13–34.

4. Andrejak C, et al. Thorax 2013;68:256–62.

5. Axson EL, et al. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2019;38:117–24.

6. Olivier KN et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:828-34

7. Roux A-L, et al. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47:4124–28.

8. Hojo M, et al. Respirology 2012;17:185–90.

9. Shteinberg M, et al. Eur Respir J 2018; 51:1702469.

10. Ringshausen FC, et al. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22:1102–05.

11. Chu H, et al. Arch Med Sci 2014;10:661–68.

12. Lim SY, et al. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e25193.

13. Ku JH, Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2020;96:114916.

14. Kwak N, et al. BMC Pulm Med 2020;20:293.

15. Smith D, et al. Thorax 2020;0:1–35.

16. Polverino E, et al. Eur Resp J 2017 ;50 :1700629.

17. Salsgiver EL, et al. Chest 2016;149:390–400.

18. Floto RA, et al. Thorax 2016;71:88–90.

19. Reynaud Q, et al. Pediatr Pulm 2020;55:2653–61.

20. Ringshausen FC, et al. Int J Infect Dis 2021;104:398–406.

21. Pyarali FF, et al. Front Med 2018;5:311.

22. Okamuri S, et al. Eur Respir J 2015;46:PA569.

23. Marras TK, et al. Eur Respir J 2016;48:928–31.

24. Brode SK, et al. Eur Respir J 2017;50:1700037.

25. Suissa S, et al. Thorax 2013;68:1029–36.

26. Winthrop KL, et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:37–42.

27. Henkle E, et al. Clin Chest Med 2015;36:91–99.

28. Suzuki H, et al. Transplant Proc 2018;50:2764–67.

29. Imoto W, et al. BMC Infect Dis 2020;20:431.

30. Kim RD, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:1066–74.

31. Reich JM, et al. Chest 1992;101:1605–09.

32. Ku JH, et al. Emerg Infect Dis 2021;27:982–85.

33. Kim SJ, et al. BMC Pulm Med 2017;17:5.

34. Dirac MA, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:684–91.

35. Colombo RE, et al. Chest 2010;137:629–34.

36. Stoller JK, et al. 2006 Oct 27 [Updated 2020 May 21]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/

37. Daniels MLA, et al. Exp Opin Orphan Drugs 2015;3:31–44.

38. Ratnatunga CN, et al. Front Immunol 2020;11:303.

39. Baldwin SL, et al. PLOS Neglected Trop Dis 2019;13:e0007083.

40. Tan Y, et al. J Infect 2021;S0163-4453(21)00261-9.

41. Hsing S-C, et al. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2013;17:928–33.

42. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/tuberculosis-surveillance-and-monitoring-europe-2019 Accessed July 2021

42. Thomson

43. Koh W-J, et al. Chest 2007;131:1825–30.

43. Lee E-S, et al. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2008;18:1207–15.

44. Falkinham JO. Clin chest Med 2015;36:35–41.

45. Falkinham JO. J Appl Microbiol 2009;107:356–67.

46. Prevots DR, et al. Annals Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:1032–38.

47. Nishiuchi Y, et al. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:347–51.

Impact of non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) on at-risk patients

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) can cause serious pulmonary disease in at-risk patients, which can have a significant impact on health-related quality of life, morbidity and mortality, and increase disease progression in patients with structural lung diseases. Understanding who is at risk can facilitate earlier diagnosis and treatment, which is crucial in preventing disease progression and lung function decline.

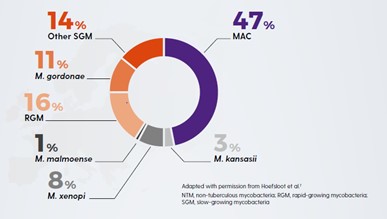

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are opportunistic infections that can cause infection at a wide range of body sites in patients who have underlying disease or are immunosuppressed.1 Inhalation of some NTM species in vulnerable people can cause non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD)2. NTM-PD can be caused by a variety of mycobacterial species, the most common of which is the Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), which comprises two main species M. avium and M. intracellulare. In one study of 62 centres in 30 countries of 18,418 isolates MAC-PD accounted for 47% of incidences of NTM-PD.3

How does NTM-PD have an impact on quality of life?

NTM-PD can be a significant burden on patients. Patients with NTM-PD, including MAC-PD, may have reduced lung function, increased morbidity and mortality, and reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) compared with the general population.3,4–11

All-cause mortality in patients with NTM-PD can be up to four times higher than the general population, independent of other factors.10–12 For MAC-PD, studies showed a pooled estimate of five-year all-cause 5-year mortality of 27%.2 NTM-PD can also cause a significant reduction in patients’ lung function.7–9 Patients with NTM-PD have been shown to experience a more substantial reduction in forced expiratory volume in 1 sec (FEV1) compared with those without NTM-PD.8 In one study where patients with mild disease were considered not to require treatment, chronic NTM infection caused a substantial decline in lung function over time.7 NTM-PD is associated with a lower HRQoL compared with the general population, with these patients demonstrating higher scores using the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and lower scores using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form Survey (SF-36).4,13 In one study, SGRQ scores in patients with NTM-PD were over 25 points worse compared with normal values.13 Another study showed that patients eventually requiring treatment for their NTM-PD had worsening SGRQ scores, suggesting an association between disease progression and lower HRQoL.4

Who is most at risk of NTM-PD?

Understanding who is at increased risk of NTM-PD can help in early recognition and diagnosis of disease. High-risk groups include tall, elderly women with a low body mass index (BMI) and abnormalities of the skeleton for example, conditions such as abnormal spinal curvatures (scoliosis, kyphosis) and structural abnormality of the chest where the sternum is pressed inward (pectus excavatum) – so-called Lady Windermere syndrome – patients with underlying lung conditions such as bronchiectasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and immunocompromised and immunosuppressed patients; exposure to NTM species is much more likely to cause disease in these groups.6,14–16

Patients with low BMI

There is an association between NTM-PD and marfanoid characteristics of elderly female patients who are taller than average with low body weight, as well as those with thoracic skeletal abnormalities; low body weight alone increases risk of NTM-PD by three-fold and thoracic abnormalities five-fold.17,18 In patients with NTM-PD, low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) has been associated with the presence of multiple NTM isolates as well as a lower chance of treatment success.4,5 In addition, patients with lower BMI are more likely to fail treatment for their NTM-PD.4

Transplant recipients

NTM can also cause disease in immunosuppressed patients who are recipients of organ or stem cell transplants.6 Rates of NTM infections in lung transplant recipients are particularly high, and have been shown to increase post-transplant mortality, with an estimated 5-year mortality of 50%.6

Patients with structural lung diseases